THE GREAT ESCAPE—it may be lazy to quote critics but for apt capsule sum-ups on this 1963 classic it’s hard to beat the contemporary reviewer from Time who ended with “The Great Escape is simply great escapism” or Sheila O’Malley’s more recent fix for Criterion that “It has entered the cultural bloodstream.” A war movie for people who don’t like war movies, and a standard bearer for those who do, its consummate professionalism, can’t lose cast, buoyant thrills and stirring, fact-based story made it the years’ 13th most popular ticket, with enduring popularity testament not only to jobs well done but in honoring the spirit, ingenuity and bravery of the real heroes it so winningly salutes. They just don’t get much “Cooler!” *

Nazi Germany. On the night of March 24, 1944, a mass breakout of Allied prisoners took place from Stalag Luft III, a camp housing captured airmen, run by the Luftwaffe. The bold saga was first popularized in a 304-page book published in 1950 by Paul Brickhill (The Dam Busters), a former Australian fighter pilot who’d been one of the captives that had worked on aspects of the ‘flight’ plan. Directed & produced for $3,800,000 by no-nonsense action ace John Sturges, the screenplay for the film adaptation was written by James Clavell and W.R. Burnett. While accurate in the basics and in many details, they injected a healthy number of audience-potential adjustments, with compositing of characters, adding on-the-rise American stars in key roles (there were few US personnel in the actual camp) and crafting sequences of high-octane adrenaline during the whirlwind third act; all tweaks acceptable for dramatic license. Extensive location filming was done in Bavaria. Running eight minutes shy of three hours, enthusiastic engagement never flags. **

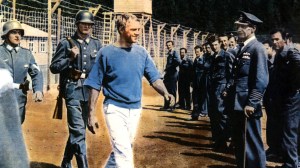

Fed up with repeated escape gambits by Allied personnel, the German High Command puts “all our rotten eggs in one basket” in a camp designed with heightened security measures. Aiming to prove them wrong and stir up a hornet’s nest inside the Reich, RAF Squadron Leader ‘Roger Bartlett’ (Richard Attenborough) aka ‘Big X’, heads up what he intends as the biggest breakout yet—200 men. Among his select are ‘Bob Hendley’ (James Garner), a genial American with a charmer’s gift for scrounging; Polish former miner ‘Danny Wolenski’ (Charles Bronson), dubbed ‘Tunnel King’, despite his attacks of claustrophobia; ‘Colin Blythe’ (Donald Pleasence), English, soft-spoken, a bird-watcher who specializes in forging, though his eyesight is failing; and ‘Sedgwick’ (James Coburn), a brassy Australian who is an ace at manufacturing gadgets. They’re shortly joined by another Yank, ‘Virgil Hilts’ (Steve McQueen), a loner, casually irreverent and not averse to pushing boundaries. Despite some disheartening setbacks, they persevere with perilous and exhaustive digging, furtive assembly-line design and construction of uniforms and civilian apparel, maps and documents, staging clever distractions and chancing risky bribes.

Though Gunfight At The O.K. Corral was his biggest box office success, and Bad Day At Black Rock the fave with critics, The Great Escape ties with The Magnificent Seven as John Sturges’ finest hours as a director. He brought along three of the ‘Seven‘ (McQueen, Bronson and Coburn), that film’s editor (Ferris Webster) and composer Elmer Bernstein. It became a key production for a number of careers. Coburn’s go at an Aussie accent is about as convincing as Dick Van Dyke’s arf’ull Cockney from Mary Poppins, but he’s such a readily likable actor & character that any slight damage is waved away. Though, as usual, he was truculent on set, Bronson shines: Sturges seemed to know how to draw keen work out of him, first in Never So Few, bettered in The Magnificent Seven, bested in this brawn-meets-fear role. Pleasence instantly wins you over as the gentle Blythe, a role that brought him international notice after ably toiling for a decade. Increasingly notable in British films since 1942, Attenborough, 39, was so strong as the driven Bartlett that it opened up his appeal to global recognition. For Garner, 33, TV popularity from Maverick hadn’t transferred to films. This broke that dam—Hendley a perfect fit for his persona and style, Jim shrewd enough to not play the Scrounger as too cute —and he scored in a trio of popular comedies that year as well—Move Over Darling, The Thrill Of It All and The Wheeler Dealers.

Certainly, the biggest chest hair coup was McQueen’s, who almost quit during the shoot before his part was buffed up to suit him. Sturges had done him solids, first on 1958’s Never So Few, where the new punk on the lot stole that war melodrama out from under Frank Sinatra (who was Frankly cool about it, one hep-cat to another), then on The Magnificent Seven, with Steve wrestling attention away from lead Yul Brynner. Pain in the butt or not (and he was), the touchy 32-year-old bad boy knew what he was doing and how to look best at it; the motorcycle bravado is one of the iconic emblems of 60’s cinema, not just boosting the charismatic actor into front-tank status to replace Brando and Elvis as a common-man rebel, but in tandem with the arrival of 007 it helped cement the concept of coiled Cool as an identity, something that’s held a grip on values-challenging imaginations well into the next century, and thru several uncool wars.

The blended acting ensemble, evocative settings, camaraderie and humor, suspense and excitement, tragedy and triumph would be qualifying enough, then Elmer Bernstein’s wonderful music score seals the deal from the opening credits to the rousing closer. Taking his emotional cues away from this would be like dumping “As Time Goes By” from Casablanca or the shark theme out of Jaws. Second only to the immortal blasts of defiance from The Magnificent Seven, his mood captures for The Great Escape—jaunty, sensitive, eerie, dynamic and proud—are a maestro’s masterpieces from a horn of plenty that blessed our ears and hearts with The Man With The Golden Arm, God’s Little Acre, Walk On The Wild Side, The Comancheros, Birdman of Alcatraz, To Kill A Mockingbird, The Carpetbaggers, The Sons Of Katie Elder, Hawaii, Animal House, Far From Heaven and Zulu Dawn.

Websters’s film editing secured the sole Oscar nomination. Let’s get real: this clockwork crafted and exhilarating epic deserved to be in the lineup for Best Picture, Director, Screenplay and, no kidding…Music Score. The domestic gross was $15,800,000, quadruple the production layout. Somehow missing this as an eight-year old (I’ll ask Dad later), this loyal Allie not catching up until United Artists re-released it in 1967 on a double-bill with The Alamo, a whopper matinee enjoyed with a pack of overjoyed pals. Fetching the soundtrack was the next logical step.

With James Donald (‘Ramsay’, the SBO, calm voice of reason, as in The Bridge On The River Kwai), Gordon Jackson (likable ‘Mac’, Intelligence), David McCallum (‘Ashley-Pitt’, Dispersal), Hannes Messemer (‘Von Luger’), John Leyton, Angus Lennie (sweet natured sacrificial lamb’ Archie Ives’), Nigel Stock, Robert Graf (flustered ferret ‘Werner’), Jud Taylor (as ‘Goff, the third token American, a little light comedy relief; Taylor later became a successful TV director), Hans Reiser, Ulrich Beiger ↓ (getting extra kilometers out of silkily pronouncing “sabotage“), Robert Desmond, Til Kuwe and Karl-Otto Alberty (US bow of ubiquitous sneering Nazi in 60’s flicks). ***

* Getting your allowances worth of spectacular action & thrills in the Promised Land of 1963—How The West Was Won, The Birds, Dr. No, 55 Days At Peking, Jason And The Argonauts. Helluva year—It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, 8½, America America, The Leopard, Cleopatra, The Victors, Tom Jones, The Balcony, The Haunting, Charade, Hud, Lilies Of The Field, The Nutty Professor, The L-Shaped Room, The Mouse On The Moon, Sammy Going South, Donovan’s Reef, McLintock!, Bye Bye Birdie, The Incredible Journey, This Sporting Life…

** Run for your life—bolting confinement in enemy territory—Grand Illusion, The Wooden Horse, The Colditz Story, The One That Got Away, The Password Is Courage, Von Ryan’s Express, The McKenzie Break, Rescue Dawn, The Great Raid.

*** Been there, lived that—shot down, Donald Pleasence at 25 endured brutal treatment as a P.O.W. for eight months. When he was 20, Hannes Messemer was a prisoner of the Russians, and, wounded, made his break by walking hundreds of miles, only to be recaptured by the British, a markedly better option. Hans Reiser (the Gestapo agent in the flick, shot by David McCallum↓) was held prisoner in Arizona; he broke out and almost got to the Mexican border. Til Kiwe (who plays a guard) had been held in Colorado: he bolted and got as far as St. Louis. Author Brickhill, one of Stalag Luft III’s 1,800 prisoners, was one of 600 who worked on the escape, though he was prevented from going on the breakout. On the other side of the global battle, co-scripter Clavell experienced three years of less-than-comfortable captivity in Singapore’s Changi prison camp, a guest of Hitler’s Japanese ally. He turned that trial of misery into his first novel, “King Rat”, filmed in 1965.

*** Been there, lived that—shot down, Donald Pleasence at 25 endured brutal treatment as a P.O.W. for eight months. When he was 20, Hannes Messemer was a prisoner of the Russians, and, wounded, made his break by walking hundreds of miles, only to be recaptured by the British, a markedly better option. Hans Reiser (the Gestapo agent in the flick, shot by David McCallum↓) was held prisoner in Arizona; he broke out and almost got to the Mexican border. Til Kiwe (who plays a guard) had been held in Colorado: he bolted and got as far as St. Louis. Author Brickhill, one of Stalag Luft III’s 1,800 prisoners, was one of 600 who worked on the escape, though he was prevented from going on the breakout. On the other side of the global battle, co-scripter Clavell experienced three years of less-than-comfortable captivity in Singapore’s Changi prison camp, a guest of Hitler’s Japanese ally. He turned that trial of misery into his first novel, “King Rat”, filmed in 1965.

“This picture is dedicated to the fifty“—thirteen of the Gestapo officers responsible for post-escape executions were later hanged. Moral: act as a Nazi, get what you deserve.