YOUNG WINSTON, as in Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill, 1874-1965, in episodes from the first 25 years of his epic life. To younger generations, he’s mostly a name that pops up in WW2 movies. But to those who were alive when he still was, he stands as a historical titan; flawed to be sure, but monumental, one of the foremost figures of the previous century, and—with no slight meant to the respective countries and peoples—most likely one of the reasons you’re not reading this in German or Japanese. If it all.

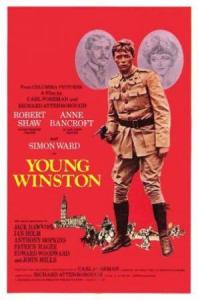

Following 1969’s Oh! What A Lovely War, Richard Attenborough’s second film as a director was this 1972 epic bio, which he also co-produced with Carl Foreman, who wrote the screenplay based off Churchill’s 1930 book “My Early Life: A Roving Commission”. The 157 minutes takes the young Winston from childhood (played by 8-year old Russell Lewis) thru adolescence (Michael Audreson, 15) into early manhood, with Simon Ward taking adult command. Anne Bancroft plays his glamorous American-born mother Jennie, Robert Shaw his rowdy, eventually malady-stricken father Randolph. A childhood marked by parental neglect and the rigor and cruelty of schooling forms a character determined to succeed, with an eye on entering politics. Prepping for that arena takes the glory road via military service in northern India, in the Sudan (including participating in the British Army’s last great cavalry charge) and in South Africa during the Boer War, where he was captured and made a daring escape that electrified the public. The tale concludes with his entering Parliament at the age of 25.

As suits a legendarily erudite and admired upper-class gentleman of distinction who, though his ma-maw was a Yankee, was most decidedly BRITISH, the presentation is stately and precise, sort of Masterpiece Theater With a Big Budget and Some Non-Bloody Battle Action. Historical biopics often tend to be the movie version of handsome two-pound coffee table books with careful, rather dry text underlining beautiful pictures neatly arranged in progression. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with that, and while the armchair approach may lull the incurious into a nap, the patient and discerning can be drawn into further exploration.  Someone whose life encompassed as much as the resolute yet puckish, stubbornly romantic, far-seeing & exasperating, lionized & controversial, tradition bound yet innovative soldier-statesman-author-bungler-national & global hero Winston Churchill could fill not just a mini-series but several—over 1,200 books have been written about him. The Attenborough-Foreman effort is a decent pass, a viable starter gun. That would be a Webley, of course.

Someone whose life encompassed as much as the resolute yet puckish, stubbornly romantic, far-seeing & exasperating, lionized & controversial, tradition bound yet innovative soldier-statesman-author-bungler-national & global hero Winston Churchill could fill not just a mini-series but several—over 1,200 books have been written about him. The Attenborough-Foreman effort is a decent pass, a viable starter gun. That would be a Webley, of course.

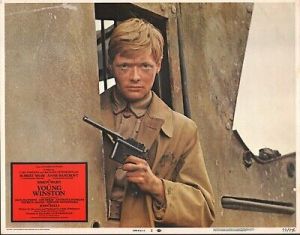

Thirty at the time, Simon Ward had started acting at 13, and had been on camera since 1960, mostly in British TV. Though a little taller and leaner, aquiline handsome Ward was a great fit for roles requiring aristocratic dash with ready wit, and he also does a good job here in mimicking the Churchill cadence in narrative voiceovers. Shaw and Bancroft are keen as expected, and the episodic treatment is studded with colorful cameos, including John Mills (as Kitchener), Anthony Hopkins (as David Lloyd George), Ian Holm and Jack Hawkins. A concession to modernity—circa ’72—is ‘The Interviewer’, done by Noel Davis (off camera), so queen-waspish he could out-sting an industrial hive farm.

The cinematographer was Gerry Turpin (Seance On A Wet Afternoon, The Whisperers, The Last Of Sheila), shooting in England, including Blenheim Palace and Sandhurst, with Wales serving for the South African segment, while Morocco did desert duty as India and the Sudan. The action sequences are fairly exciting, taking in Winnie’s inaugural combat during a fierce hillside skirmish in India, the 1898 Battle of Omdurman in the Sudan (enlist 1939’s grand The Four Feathers) and the follow-up gallant-foolish cavalry charge, and finally the train derailment ambush, capture and knotty escape during the mess made in South Africa. One unfortunate debit is the parade-ground music score from Alfred Ralston, hollow-jolly stuff even cheesier than the one John Addison marred A Bridge Too Far with.

“I say, sir, we must not regard modern war as a kind of game in which we may take a hand and with good luck and good management play it rightly for an evening and when we have had enough, come safely home with our winnings. Oh, no, sir. It is no longer – a game. A European war cannot be anything but a cruel and heartrending struggle, which, if we are ever to enjoy the bitter fruits of victory, must demand, perhaps for years, the whole manhood of the nation, the entire suspension of peaceful industries, and the concentrating to only one end – of every vital agency in the community. Aw, yes, it may be that the human race is doomed, never to learn from its mistakes. We are the only animals, on this globe, who periodically set out to slaughter each other, for the best, the noblest, the most inescapable of reasons. We know better. But, we do it again and again, in generation after generation.”

Rather dutifully, Oscar nominations were pinned to the Screenplay, Art Direction and Costume Design. Though understandably big in Britain, in the States it lagged at 55th place in 1972, the $6,500,000 gross not cricket after a lordly expenditure; no cost figures are available but a valid stab is five to ten million.

The pedigree-borne battalion in support includes Edward Woodward, Laurence Naismith (as Lord Salisbury), Patrick Magee, Basil Dignam, Colin Blakely, Nigel Hawthorne, Robert Hardy, Norman Rossington, James Cosmo and Jane Seymour.

* Ward: “That was a frightening role. You were playing someone whom everyone had very strong feelings about. As a movie, it had the most extraordinary mixture of adventure – the fighting, riding, running up and down mountains – and some wonderful dialogue scenes shot at Shepperton.” “I didn’t look right for American movies. I would have ended up playing depressed gay marquesses. I was too young for the butler. I was not craggy enough for the conventional leading man.” “I’ve never desperately wanted anything, neither fame nor riches.” We’re fans, from this movie, the all-time best version of The Three Musketeers and the stunner spectacle Zulu Dawn. He passed away at 70 in 2012.