CIMARRON rumbled—many would say stumbled—across the wide screens of movie palaces and drive-in’s in December, 1960, the last of the year’s mostly impressive westerns and one of 60’s costly epics. Vying for attention with the grand-scale blockbusters Spartacus, Exodus and The Alamo, this 147-minute remake of the 1931 winner for Best Picture (the only western to claim that until 1990’s Dances With Wolves) laid on the dough like those others but while they took, respectively, 2nd, 4th and 5th place at the box office, Cimarron dried up at 43rd, its $6,600,000 gross a debacle measured against a price tag of $5,421,000. Oscar nominations were finagled for Art Direction and Sound, but reviews were as weak as the receipts. A regrettably flawed movie, for sure, but it is more entertaining than its lame reputation indicates, contains many fine moments and is distinguished by one truly spectacular sequence. *

Edna Ferber (1885-1968) wrote sweeping novels about facets of the American experience, bestsellers in their day; seven were turned into movies. Big places figure–the Mississippi River, Wisconsin, Texas, Alaska. In the 300 pages of “Cimarron” (the #1 novel of 1930) the story covers Oklahoma from Territory into Statehood, thru the Land Rush of 1889, building new cities and the oil boom, up to the early 1920s. The splashy color remake was scripted by Arnold Schulman (Love With The Proper Stranger, The Night They Raided Minsky’s, Tucker: The Man and His Dream) and had two directors. Western ace Anthony Mann worked on it and has screen credit, but he dismounted in disgust over how MGM chief Sol Siegel and producer Edmund Grainger interfered and overrode. Mann left the 19th century Midwest to 20th-century desk jockeys for 11th century Spain and the colossal El Cid. Charles Walters, noted for musicals (Easter Parade) and comedies (Please Don’t Eat The Daisies), took over and finished it, reshooting quite a bit, sans credit.

1889. Cowboy-gone-civilized ‘Yancy Cravat’ (Glenn Ford, 43) takes beaming bride ‘Sabra’ (Maria Schell, 33) from her cosseted life to a speculative one in the grand opening of the Oklahoma Territory, kicked off with a gigantic crowd stampede for new land to stake claims on. Sabra has quite a learning curve given the primitive conditions and often primitive attitudes and behaviors of the polyglot mix of ‘Sooners’. Among them are Yancy’s old flame, good-time gal ‘Dixie Lee’ (Anne Baxter, 36), untamed rowdy ‘The Cherokee Kid’ (Russ Tamblyn, 24), poor sodbusters the Wyatt’s (Arthur O’Connell, Mercedes McCambridge) and their teeming brood of kids, and ‘Bob Yountis’ (Charles McGraw), a vicious racist brute. Sabra also has to deal with Yancy, who may be a frontier Renaissance Man (cowboy, gunman, gambler, college grad, lawyer, editor) he’s also possessed by enough wanderlust for five men.

Buffs can discern the divergent directorial styles of Mann and Walters, but even casual viewers will see the patchwork effect that shows up in the camerawork (especially the lighting), set design and locales (nice outdoor scenic values—Arizona standing in—repeatedly contrasted with obvious studio backdrops), and sloppy chronological leaps. Franz Waxman’s score is okay (westerns not his forte), but someone made the call to open with a lame title tune from The Roger Wagner Chorale. Though not atrocious like the stinkers hurting Alvarez Kelly or The Way West, it’s bland and old-fashioned. Done right (High Noon, Gunfight At The O.K. Corral, 3:10 To Yuma) that sort of intro can masterfully make a mood. Overdone, you want to leave the room.

Cravat’s mercurial character leaves the scene long enough and often enough that the story really belongs to Sabra, with neither as appealing as needed to hold close such a wide canvas saga; Ford and Schell (she’d just done the excellent The Hanging Tree) do their best against the inconsistent script and editing. Tamblyn is very good as the self-destructive outlaw, McGraw at least as despicable here as he was in Spartacus, McCambridge is always welcome, Vic Morrow gets a taut scene as one of Tamblyn’s gang.The surprising standout is Anne Baxter, warm and restrained this time around.

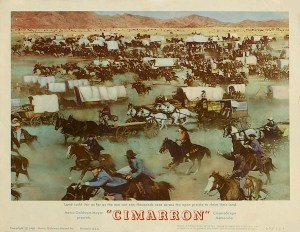

The ending is anti-climactic not just because of the clunky editing but because the clincher comes early in the first act, with the land rush. The studio bragged that it deployed 1,000 extras, 700 horses and 500 wagons and buggies: even if that’s an exaggeration it sure looks like that many are racing hell-for-breakfast, with a load of dangerous looking full-tilt riding, team driving and accompanying pile-up crashes and falls. A showpiece dazzler.

Jostling for purchase in the supporting swarm: David Opatoshu, Harry Morgan, Robert Keith, Aline McMahon, Edgar Buchanan (negligible part), Buzz Martin, Vladimir Sokoloff, Royal Dano (there & gone), Mary Wickes (wasted), Charles Watts, Eddie Little Sky, L.Q. Jones (no lines, one closeup and adios) and Ivan Triesault.

* Edna Ferber, displeased: “I received from this second picture of my novel not one single penny in payment. I can’t even do anything to stop the motion-picture company from using my name in advertising so slanted that it gives the effect of my having written the picture … I shan’t go into the anachronisms in dialogue; the selection of a foreign-born actress…to play the part of an American-born bride; the repetition; the bewildering lack of sequence….I did see Cimarron…four weeks ago. This old gray head turned almost black during those two (or was it three?) hours.” She was doubtless double-irked by the same year’s film failure of her most recent book, Ice Palace.

Racing form—the 1931 version purportedly deployed 5,000 extras and cost $1,433,000, a hunk of dough during the Depression. The bread came back but it took a re-release in 1935 to do so. Cogerson lists a gross of $3,600,000 and 14th place in 1931. Oscars for Best Picture, Writing and Art Direction, nominations for Direction (Wesley Ruggles), Actor (Richard Dix), Actress (Irene Dunne) and Cinematography. At the time critics raved, today its rep has diminished badly. The land rush sequence remains a whopper. Ron Howard staged it again for Far And Away in 1992. Cogerson ranks it 21st at the box office, taking $58,900,000 domestic, $79,000,000 more abroad. The $60,000,000 budget (double and then some for auxiliary costs) left it a dud, and reviews were not positive. The Oscars looked elsewhere. The land rush scene works, unleashing Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman among 800 extras, 900 horses, mules and oxen and 200 wagons.

The actual Oklahoma Land Rush on April 22, 1889 involved more than 50,000 people. Maybe 35 perished during the wild scramble. Beyond the bright fun and great tunes of the classic hit musical Oklahoma!, the less-lilting state of the State’s oil tapping can be examined in War Of The Wildcats, Tulsa, Oklahoma Crude and Killers Of The Flower Moon.