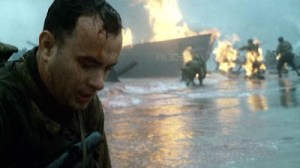

SAVING PRIVATE RYAN—“I’ll see you on the beach“, US Ranger Captain ‘John Miller’ (Tom Hanks) assures his nervous men in the landing craft that’s bearing them to the French coast on the morning of June 6th, 1944. What he and they see on the beach—those that actually get onto and across it—is a nightmare of fury, confusion and pain, otherwise known to history as the desperate amphibious landing on a strip of Normandy sand code-named ‘Omaha’. For awestruck movie audiences of 1998, and succeeding waves of viewers at home, director Steven Spielberg’s instant classic opening sequence was/is about as close to the intensity of mass combat as they ever want to get.

Normandy, France, early June, 1944. A few days after the beachhead is secured, Miller and a squad from what’s left of his company are presented with a fresh and novel task. Unlike the cauldron of D-Day, a world-shaking, game-changing battle on a giant scale, this job is tiny and personal, ordered back in the States by the Chief of Staff, Gen. George C. Marshall (a neat cameo from Harve Presnell, 64) as a mission of mercy: locate and ‘save’ Pvt. Joseph Ryan’, whose three brothers have just been reported killed in action. Miller’s squad bristles at the risk, but orders are orders, and they plunge into the contested countryside. Joining Miller are stoic veteran ‘Sgt. Mike Horvath’ (Tom Sizemore) and understandably truculent enlisted men ‘Reiben’ (Edward Burns), ‘Mellish’ (Adam Goldberg), ‘Jackson’ (Barry Pepper), medic ‘Wade’ (Giovanni Ribisi), ‘Caparzo’ (Vin Diesel) and inexperienced ‘Upham’ (Jeremy Davies), interpreter.

The script by Robert Rodat (Fly Away Home, The Patriot)—with uncredited contributions from Frank Darabont (The Shawshank Redemption, The Green Mile) and Scott Frank (Get Shorty, Out Of Sight)—drew inspiration from the story of the four Niland brothers, who figured in a D-Day book from WW2 historian Stephen Ambrose, and also from the better known tragedy of the five Sullivan brothers, all perishing when their ship was sunk in 1942 (see 1944’s moving The Fighting Sullivans). The sibling thread—danger to loved ones an obvious audience identification hook—is really just connective tissue for the wider communal grip of the epic, a valedictory salute to the men and boys of an earlier generation who went into the jaws of Hell to face down monstrous tyranny.

Shot in Ireland and England for $70,000,000, it isn’t a sweeping semi-documentary spectacle like 1962’s The Longest Day, but instead conveys the breadth of the invasion with just a few ‘big’ shots; after the staggering opener, the focus is on a small group involved in several skirmishes (typically great Spielberg set-pieces) and then, as demanded by drama, a final do-or-die battle in a village after locating the title trooper (played by Matt Damon). As the still dazzling The Longest Day was in its Boomer era, ‘Ryan‘ is widely accepted as a modern classic, impact multiplied by the loosening of what-can-now-be-shown being plainly obvious in the carnage displays ever more acceptable and realistic since Bonnie And Clyde and The Wild Bunch (i.e Vietnam)—and pointedly overdue after decades of exciting war movies that, however well done, were constrained to soft-pedal the horrific blood & guts aspect to extol the ‘glory’, please the tenor of the day and secure the vital cooperation of the all-consuming military.

For the most part, a helluva show: the cast is strong, the direction, editing, cinematography (Janusz Kaminski), sound effects and art direction outstanding. Hanks, while in standard war flick fashion is too old at 41, delivers his usual pitch-perfect performance: his brief, solitary and silent breakdown-and-recover moment is masterful. Likewise a bit on in years for their cameo spots are Ted Danson, 50, and Dennis Farina, 53. The action scenes are so galvanizing and most the actors so good (Sizemore never better, great work from Goldberg, Ribisi and Pepper) that it’s only later you tentatively raise your hand with pesky questions…

…like (1) how did the news of a particular three deaths (among thousands) reach D.C. in a day or so? (2) brilliant warlord Marshall may well have had feelings about one family’s losses, but he had somewhat bigger problems to deal with (3) Miller’s decision to release a German captive who’d just helped kill one of his men is neat drama but bogus reality (4) wussy Upham—a ‘morality’ sop to the battalions of half-men creampuffs of today—is not only irritating (Davies makes Brad Davis from Midnight Express seem like Robert Mitchum) but there simply is no f’ing way a recruit in 19 & 44 would be clueless about the meaning of ‘FUBAR’, and (5) newcomer Damon, 27, just isn’t sufficiently compelling as the source of all the trouble. **

The above are, however, nitpicks next to the overall power of the show. The grosses tallied $216,500,000 at home, the year’s #1 performer, with a further $265,300,000 internationally. The Academy Awards recognized it with best Director, Cinematography, Film Editing, Sound and Sound Effects Editing, and had nominations for Best Picture, Actor (Hanks), Screenplay, Music Score, Production Design and Makeup. We’ll say aye to the five wins and the noms for Pic and Tom, but ix-nay on the last four. Once again, we were not consulted. Uh, kinda like the Army. ***

169 wrenching minutes, with Leland Orser (the traumatized glider crash survivor), Paul Giamatti, Nathan Fillion (the wrong Ryan), Joerg Stadler (‘Steamboat Willie’, deceptive prisoner), Harrison Young (67, as Ryan, older, movingly morphed from Damon, 27), Bryan Cranston and Anna Maguire (the little French girl who angrily slaps her papa).

* Above & Beyond—as startling and immersive as this film is, we think Spielberg and Hanks deserve more praise for subsequently producing the stellar mini-series Band Of Brothers and The Pacific, nigh unbeatable in their realism, layered characterizations and impact that rewatches don’t dispel but further enhance.

** FUBAR alert!—in the IMDb under their ‘Goofs’ section they list a whopping 131 continuity errors, 52 factual strays, 43 ‘revealing mistakes’, nine anachronisms and 31 miscellaneous flubs. Well, gosh, Wally, lots of movies are laced (or filled) with goofs of one sort of another, and while we’re somewhat surprised by some of the f-up’s in this one (this is apart from the above issues with the likelihood situation presented by the script) we’ll cut Steven’s Army some slack because his tribute races past with such momentum and the editing  is so adroit that it’s a reminder that film-making is done in hundreds—thousands—of individual bits and pieces involving intense, high-pressured and costly cooperation from multiple sources, efforts and ingenuity, dreams and sweat, expertise and guesses that are then collected and collated into what hopefully is not just cohesive but convincing, not a documentary (they’re made of choices, too, and aren’t infallible) but an artistic representation of not fact, but ‘truth’. They’re intended for emotional impact, a sense of immediacy and connection, for entertainment chiefly, with enlightenment a lucky bonus. Unless you’re a budding editor, director or a non-industry know-it-all or basic killjoy, they are not designed to be microscopically analyzed in order to hone your craft (defensible), emulate or ripoff others in the field (questionable) or, worst, make your lonely self come off as an insider/historian/wit/genius/jerkoff by cheesily belittling other peoples accomplishments, 99% of which are quite likely beyond your own (call this smugness for what it is: chicken—t).

is so adroit that it’s a reminder that film-making is done in hundreds—thousands—of individual bits and pieces involving intense, high-pressured and costly cooperation from multiple sources, efforts and ingenuity, dreams and sweat, expertise and guesses that are then collected and collated into what hopefully is not just cohesive but convincing, not a documentary (they’re made of choices, too, and aren’t infallible) but an artistic representation of not fact, but ‘truth’. They’re intended for emotional impact, a sense of immediacy and connection, for entertainment chiefly, with enlightenment a lucky bonus. Unless you’re a budding editor, director or a non-industry know-it-all or basic killjoy, they are not designed to be microscopically analyzed in order to hone your craft (defensible), emulate or ripoff others in the field (questionable) or, worst, make your lonely self come off as an insider/historian/wit/genius/jerkoff by cheesily belittling other peoples accomplishments, 99% of which are quite likely beyond your own (call this smugness for what it is: chicken—t).

*** Collateral damage from the barrage—the year’s other big war movie, the stunning, elegiac The Thin Red Line also went up for Oscars, seven including Picture, yet claimed none, and only reached 57th at the box office, Terence Malick’s challenging meditation shouldered aside by the focused, jarring narrative drive of Spielberg’s in-your-face audience grabber. As with Saving Private Ryan, the flaws in The Thin Red Line are forgiven because most of it is terrific, a magnificent artistic achievement.