KUNDUN, one of Martin Scorsese’s least-seen films, is the critically applauded, corporate-hijacked centerpiece of what amounts to his unofficial religious/spiritual trinity, this beautifully mounted 1997 offering flanked by 1988’s The Last Temptation of Christ and 2016’s Silence. The “blasphemy” (to those rankled by whatever that concept constitutes) of the first film and the agonized ecstasy of the last both dealt with Judaeo-Christian trials and tribulations. This one entails Buddhism and its traditions confronting modernism (the repressive end of it), the former represented by once-independent Tibet and the 14th Dalai Lama, the latter by Communist China’s sudden post-WW2 arrival under Mao Zedong.

The storyline covers 1937 to 1959. It begins with lamas testing and selecting a child (the self-selection presumed inherent) who will become the political spiritual leader of Tibet. It climaxes with the Dalai Lama leaving the country in exile when Mao’s victorious Communists locked in mass-scale repression.

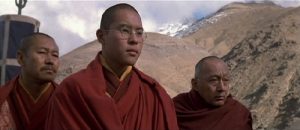

In the bulk of the film, the Dalai Lama as an adult is played by Tenzin Thuthob Tsarong; as a child he’s interpreted by Gyurme Tethong, Tulku Jamyang Kunga Tenzin and Tenzin Yeshi Paichang. Melissa Mathison (The Black Stallion, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial) wrote the script, with Scorsese directing it as an appropriately meditative epic. Cameraman Roger Deakims shot mostly in Morocco (Tibet off-limits) with some scenes lensed in British Columbia and Idaho. The running time is a measured 134 minutes, and well-deserved Oscar nominations came for Cinematography (including a powerful pull-back crane shot of slaughtered monks that recalls the famous Atlanta rail-yard scene in Gone With The Wind), Art Direction, Music Score (superb work from Philip Glass) and Costume Design.

After all the loving care, patient effort and an expenditure of $28,000,000, Disney CEO Michael Eisner (speaking of cold-hearted dictators) suddenly developed a severe case of base-line cowardice over China’s objections. The prospect of lost revenue trumped pesky humanitarian values; dumped into a release-strangled mineshaft the grosses came to just $5,687,000. *

With Gyatso Lukhang, Jurme Wangda, Tsewang Migyur Khangsar, Tencho Gyalpo. Robert Lin impresses as a decidedly unsympathetic Mao Zedong, of the few cinematic representations of Mao (Conrad Yama in The Chairman and Tang Guoqiang in Mao Zedong 1949, Hundred Regiments Offensive and The Battle at Lake Changjin).

* Mickey Rat—Eisner:…”a stupid mistake….The bad news is that the film was made; the good news is that nobody watched it. Here I want to apologize, and in the future we should prevent this sort of thing, which insults our friends, from happening.” All’s fair—when all that matters is money.

I can’t imagine a better dramatic film could be made about His Holiness. Yet there is another tale untold in dramatic form: that of the Tibetan guerillas trained by the CIA in Colorado and deployed to Tibet for a tragic, hopeless cause. The last holdouts, hiding in a remote province of Nepal, put down their weapons in the early 1970s after a radio message from His Holiness asking them to give up the fight.