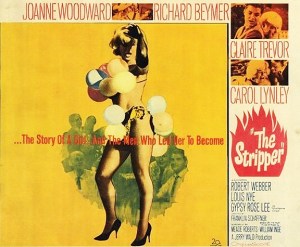

THE STRIPPER, not a salacious expose like its misleading title would indicate, but another one of those American Gothic downers about lonely, aging women, written by inner-self-projecting gay men, this time set in the repressed Midwest instead of the steamy South, conjured by William Inge rather than Tennessee Williams. 20th Century Fox production head Buddy Adler, betting on a hit like Inge’s Picnic and Bus Stop, plunked down $400,000 for the rights to his 1959 play “A Loss Of Roses” even before it opened on Broadway. That much green would be about $4,338,000 in 2025 (wait ’til next year). Oops, Buddy, the play closed after twenty-five performances. Initially the property was scoped as a vehicle for Marilyn Monroe and Pat Boone (stop laughing); they both turned it down. When it finally went out in 1963 Joanne Woodward had the trapped-in-life’s-amber role of the sort previously put under the melodrama microscope by the flamboyant likes of Vivien Leigh, Anna Magnani and Geraldine Page. A good choice. Unfortunately, rather than being pawed over/brought back to life/discarded by territory scouts Marlon Brando or Paul Newman, the extra dose of man misery was tooth-pasted on by the earnestness-on-display of Richard Beymer. “Next!” *

Part of a team of low-yield traveling entertainers, struggling actress ‘Lila Green’ (Woodward, 33) is oarless on a Kansas creek. Ripped off by her crass manager/bedfellow ‘Ricky Powers’ (Robert Webber, doing one of his perfected bastards) and cut loose by her troupe mates ‘Ronnie Cavendish’ (Louis Nye, ever odd) and ‘Madame Olga’ (Gypsy Rose Lee, lively), Lila finds a temporary hometown berth with ‘Helen Baird’ (Claire Trevor), a friend from high school. The new wrinkle to iron is Helen’s teenage son ‘Kenny’ (Beymer, 25 doing 18) who right off the bat finds outgoing, naturally sexy Lila more interesting than neighborhood cutie/tease ‘Miriam Caswell’ (Carol Lynley), let alone goofus ‘Jelly’ (Michael J. Pollard), his gas station co-worker. The boy-meets-bombshell situation brings, as expected, yearning, spurning and learning, especially when prick Ricky slides up in a convertible with the escape/trap lure of a good paying gig as a stripper.

The script adaptation by Meade Roberts (film versions of Tennessee Williams’ The Fugitive Kind and Summer and Smoke) is weighed down by the been-there feeling, dreariness not helped by shooting in flat black & white (the fictional Kansan town is Chino, California). First-time feature director Franklin J. Schaffner lucked out with the cast (Beymer the weaker link); Woodward, adorned with a blonde wig and sexed-up more than usual, is spot-on, and veteran Trevor is quietly strong as the concerned friend and mother. One issue faced not just by Lila, but by Woodward and the viewer is how well they and the audience deal with the baked-in-cruelty of the available men being Richard Beymer, Robert Webber, Louis Nye and Michael J. Pollard. Yeesh. Made today and Lila would drop those dweebs and make a beeline for Lynley’s nymph next door. Meanwhile, a few states away, Joanne’s mate Paul Newman was occupied trolling Patricia Neal in Hud.

Made for north of $2,175,000, that title gambit (the very tame strip act biz shows up for a few of the last ten minutes) and the insinuating advertising posters and blurbs were likely done to juice up interest on the heels of the previous year’s Gypsy (Natalie Wood playing real life stripper Gypsy Rose Lee), 62’s huge instrumental pop hit “The Stripper” from David Rose (included below, just for the My Blog heck of it), and the basic bait & switch lure of the subject. 61st in ’63, the box office of $4,300,000 was a disappointment.

Jerry Goldsmith did the score. An Oscar nomination went to the Costume Design. With Susan Brown and Bing Russell. 95 minutes.

* Woodward had taken a motherhood break for a few years, and the weak box office and reviews of this and a wan comedy (A New Kind Of Love, with hubby Paul) didn’t help her regain career momentum. Neither did her three subsequent pictures, Signpost To Murder, A Big Hand For The Little Lady (fun) and A Fine Madness. But she (and Newman, directing) slammed a home run in 1968 with the sublime Rachel, Rachel. For the oft-criticized Richard Beymer, the huge success of West Side Story didn’t reap expected dividends. Though he was one of the 42 stars of the mega-hit The Longest Day, his other releases—Five Finger Exercise and Hemingway’s Adventures Of A Young Man—were considered losers, and he carried much of the overly harsh critical shellacking. After The Stripper he took himself off the board and out of the Movie Star mine field. Beymer was hardly terrible, but you either have gravitas and charisma or they’ll find someone else who does. It’s called Show ‘Business’ for a reason.