WUSA, an interesting, frustrating dud, is both ahead of its time—keyed on the slow-moving coup of right-wing media manipulation, radio in this instance—and perfectly of its time as one of the waterfall of anti-Establishment pictures that pleased or riled audiences in 1970. If nothing else it showed that if conservative John Wayne could shoot himself in the boots with rah-rah nonsense like The Green Berets then liberal Paul Newman could mess up a message with this jumbled gumbo. Having aced directing Paul’s classic Cool Hand Luke, Stuart Rosenberg was assigned. Robert Stone’s screenplay was based on his novel “Hall Of Mirrors”. Newman-co-produced as well as starred, with wife Joanne Woodward and a well-picked supporting lineup.

“Fellow Americans. Let us consider the American way. The American way… is innocence. In each and every situation we must display an innocence that is so vast and awesome that the entire world is reduced by it. When our boys drop a napalm bomb on a cluster of gibbering slants, it’s a bomb with a heart. And inside the heart of that bomb, mysteriously but truly present, is a fat, little old lady on her way to the world’s fair. And that lady is as innocent as she is fat and motherly.”

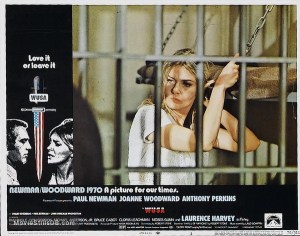

In New Orleans, alcoholic drifter ‘Rheinhardt’ (Newman) links up with life-scarred prostitute ‘Geraldine’ (Woodward) and they move into a ramshackle apartment. An experienced disc jockey, Rheinhardt is hired by WUSA, a ‘patriotic’ station, where along with spinning records he reads news (as the management sees it) and editorials. One of the apartment neighbors is ‘Rainey’ (Anthony Perkins), a nerves-jangled former Peace Corps worker who has thankless work doing surveys among the city’s poor, predominately black underclass. His growing suspicions about his ill-defined job and its shady crumb trail lead him to question the cynical Rheinhardt about WUSA’s one-sided pitch and their ultimate end game. As increasingly sullen Rheinhardt gets more defensive and booze-basted, the kind-hearted, initially hopeful Geraldine worries that she’s picked just another black marble.

Commendable—the premise: generalized societal corruption and class/race dissatisfaction fertile ground for misinformation posing as patriotism. The settings: bleak but compelling, no sort of commercial for New Orleans, it never looked seedier or more decrepit. The acting: mostly good, some very good. Woodward, expertly outfitted with a subtle facial scar, is open and unaffected, her grasp of Geraldine’s wary naivete is intuitive without any window dressing. Laurence Harvey’s brief, knowing turn as a preacher-huckster is the best thing he’d done in five years. The great Pat Hingle sells genuine insincerity with a shark’s smile and the cold confidence of the powerful. All of the many smaller roles come across to good effect.

Regrettable—Newman’s fine but the corrosive Rheinhardt character is the most adamantly unlikable he ever played; even Hud‘s an easier guy to spend time with. Perkins varies between moments that feel on target and many that are mannered up with his tendency to too often go for a ‘tic’. Maybe something was lost in the editing (Stone’s novel ran 409 pages) but after loading the characters up with personal, depressing and often aimless dialogue bouts, there’s next to nothing shown of how the guts of the presumably quasi-fascist operation of WUSA really works. We are just left to assume it’s bad. Then everything falls apart in a chaotic blur in the climactic stadium panic sequence; so jagged and overblown it’s almost comical. And the ultimate payoff isn’t even an effective ‘chill’ warning (as in, say The Parallax View) but just hopelessness. After a long buildup, the movie—in some contorted misread of direction, editing and/or script—throws itself away.

The original preview ran 190 minutes (please, no), cut down to the released 115. Stinging reviews and a dinging 57th place weren’t punishment enough; at $4,700,000 to make, more than twice that was required to break even. The gross was just $4,800,000.

Initially Newman stood up for it: he let Rosenberg slide and hired him for Pocket Money and The Drowning Pool. Twelve years later he fessed it as “a film of incredible potential which the producer, the director and I loused up. We tried to make it political, and it wasn’t.” With apologies to the much-missed star/activist/entrepreneur/good guy, surely it was political and surely they loused it up. Meanwhile, the venal types and ruinous creed they were signalling about have succeeded beyond their sickest fantasies.

With Moses Gunn, Wayne Rogers, Cloris Leachman (touching as Geraldine’s hapless, handicapped friend), Don Gordon (as a bearded, gibberish spouting hippie stoner), Michael Anderson Jr. (hippie #2, you won’t recognize him), Leigh French (proto-hippie chick comedienne as hippie #3), Robert Quarry, Clifton James, B.J. Mason, Susan Batson (intense bit as a end-of-her-rope slum dweller), Skip Young, Bruce Cabot (did Duke Wayne’s drinking buddy know what sort of movie he was in?), Geoffrey Edwards, Hal Baylor, John Mitchum, the Preservation Hall Jazz Band, Kristin Anderson, David Huddleston, Jesse Vint, Diane Ladd.

* The Artists Strike Back, 1970—MASH, Little Big Man, Woodstock, Catch-22, Getting Straight, Myra Breckinridge, The Great White Hope, …tick…tick…tick…,Gimme Shelter, The Liberation Of L.B. Jones, Brewster McCloud, Soldier Blue, The Revolutionary, R.P.M.