FOURTEEN HOURS runs 92 minutes in a superior 1951 thriller directed by no-nonsense craftsman Henry Hathaway. The screenplay done by John Paxton (Murder My Sweet, Crossfire, On The Beach) was based off a magazine article (“That Was New York: The Man on the Ledge”) describing a 1938 public suicide leap in Manhattan that tied up 300 policemen and was watched by a crowd of 10,000. Though 156th place (gross $2,000,000) doesn’t seem like much, the movie drew a good deal of notice for the superb performance of the desperate protagonist by Richard Basehart, for Hathaway’s expert handling and for its casting—the supporting lineup is jam-packed with familiar faces and numerous future stars. One Academy Award nomination was drawn, for Art Direction. The year had a stellar lineup for Best Actor nominations (Bogart, Brando, Clift, March, Kennedy) but Basehart was every bit as deserving.

“Everybody lies to me!”

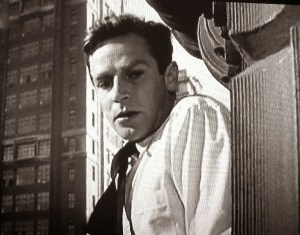

New York City, gearing up for its St. Patrick’s Day parade. Traffic cop ‘Charlie Dunnigan’ (Paul Douglas) is first on the scene when a hotel room service waiter discovers a guest perched on a foot-wide ledge, 15 floors over the street. As police converge, the Deputy Chief (Howard Da Silva) and a psychiatrist (Martin Gabel) detail Dunnigan, a plain-spoken ‘everyman’ guy, to try and coax the visibly distraught ‘Robert Cosick’ (Basehart) to not do what he seems bent on: ending his inner torment in a spectacular fashion. Crowds throng to watch the drama, newsmen converge, and Cosick’s parents are brought in: they’re seemingly as messed up as their son.

Cosick is presented as “a young man” and even though he was 36, Basehart convinces as someone a decade or more junior. It’s a remarkably persuasive performance, blending shredded nerves, wounded decency, angry determination, trust, betrayal and confusion, touching and sympathetic without artifice. A number of the era’s emergent ‘method’ actors would have tic’d, mumbled and gnashed audience identification away from the man’s pitiable plight and wished the agonizing actor would go ahead, take the fall and put us out of his misery. Thankfully, Basehart’s interpretation is honest and real. It was a particularly difficult job of work for him: his wife died from brain tumor during the shoot. That personal loss was contrasted with a career in gear, 1951 gave him other strong roles in House On Telegraph Hill, Samuel Fuller’s taut Fixed Bayonets! and the excellent Decision Before Dawn.

Douglas, Da Silva and Gabel are quite good, ditto Robert Keith as the weakling father and especially Agnes Moorehead, killing it as the hysterical and self-aggrandizing mother. Costick’s reasons for suffering are hinted at rather than spelled out; viewers can impart what they see fit. As to agendas: generally mentioned for his numerous top quality westerns and rugged adventures (and a renowned temper on set), Hathaway was equally adept at urban thrillers (Kiss Of Death, Call Northside 777, Niagara) and his pacing and marshaling of details here fits in with several semi-documentary winners he piloted. Like Robert Wise and Henry King, he served the story rather than using assignments to flout a ‘personal vision’ that auteur cheerleaders insist & exhaust into the keyboard ether.

Back to the cast—debuting in small roles are Grace Kelly, 21, Debra Paget, 17, and Jeffrey Hunter, 24. Among future notables in bit parts try to spot Richard Beymer (13), John Cassavetes (21, debut), Ossie Davis (34, 2nd film), and Janice Rule (19, debut). Brian Keith, 29, was an extra. He isn’t listed in the credits for the film and his own credit roll doesn’t show it, but we could swear spying Leo Gordon as a cop: need Blu-ray and freeze-frame to win my bet. Other worthies in play include Barbara Bel Geddes, James Millican, Frank Faylen, Jeff Corey, Brad Dexter, Harvey Lembeck (28, 2nd film), John Doucette, Parley Baer, Leif Erickson, John Randolph, Willard Waterman and Joyce Van Patten (17, debut).