THE PRISONER OF SHARK ISLAND, beneath its title, imprints that it is “Based on the life of Dr. Samuel A. Mudd”. ‘Based’ in this case the operative word; posterity better served if ‘loosely’ had preceded it. The story begins in April, 1865; the movie came out 61 years later in 1936, and makes its case with what was known at the time. Contrary evidence brought to light since takes the ‘inventive’ screenplay to the woodshed, but the cinematic skill sets around it still carry impact, even if you wince at some ‘antiquated’—make that offensive—racial stereotypes. Darryl F. Zanuck produced it. Nunnally Johnson wrote it. John Ford directed it. “Print the legend.” *

On the night of April 14, 1865, a man with a badly injured leg shows up at the Maryland home of Dr. Samuel Mudd (Warner Baxter). Mudd treats the man, who spurs away into the dark. The man is John Wilkes Booth and he’s just assassinated President Abraham Lincoln. Ignorant of who he’s helped, Mudd is arrested as part of the plot Booth led. While others involved are hanged in a one-sided show trial, Mudd is sent life imprisonment on a tropic island hellhole in the Gulf of Mexico. His distraught wife makes a desperate attempt to free him, but it takes the impartial forces of nature (yellow fever and a hurricane) to roll the wheel of justice back to grinding in something like the right direction.

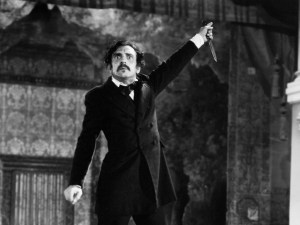

Thanks to the basic gripping historical outline, to Ford’s eye for composition, casting, mood and his essentially liberal lean to justice, to cameraman Bert Glennon (The Scarlet Empress, Stagecoach, Drums Along The Mohawk) and to some excellent performances, the movie bests its dated and distressing but not destructive flaws. The lengthy escape sequence is a quite impressive display of tension and excitement with camerawork, editing, effects and some bravura physicality working in fierce harmony. Baxter, 46, delivers with heartfelt strength and sensitivity in the lead; it’s one of his best performances. The beaming lady playing his (script misnamed) wife is 25-year-old Gloria Stuart, six decades before she’d be re-recognized, worldwide, for her grace role in Titanic. Knocking one down with gleaming malevolence is John Carradine, 29, as a sadistic guard. Duly impressed, Ford would cast him nine more times. Carradine was one of the few actors who never quailed under ‘Pappy’s’ bullying.

Then, well, there’s Nunnally Johnson’s script—what it puts in and what it leaves out—and attitudes of the day best left in the day. The opening scroll declares “The years have at last removed the shadow which rested upon the name of Dr. Samuel A. Mudd of Maryland, and the nation which once condemned him now acknowledges the injustice it visited on one of the most unselfish and courageous men in American history.”

Uh, kinda sorta & a lotta nada. As for facts–not the ‘alternate’ kind—Booth shot Lincoln; Mudd was tried as an accomplice; He was sent to prison, tried to escape and failed, then helped battle disease during his confinement. Almost everything else is ripped strips from whole cloth.

From the get-go—the title itself, while dramatic, is misleading, since ‘Shark Island’ was/is actually Dry Tortugas, islets 70 miles west of Key West, Florida. Today it and Ft. Jefferson (Mudd’s prison) are a national park. That Mudd was an ardent Reb, a slaver from a line of like and knew Booth more a bit before the fateful night are pesky items missing in action. There’s a tiresome never-say-die “old Confederate Colonel” played by Claude Gillingwater. That fits with the era’s movies catering to Southern audiences (those Civil War memories burning on) and aspects of ‘the Lost Cause’ to ensure box office. Black characters are kept in servitude to pop-eyed stereotypes, some so outrageous they’re nearly satirical of the trope. A “good” ‘boy’ comes from Ernest Whitman as a “loyal” ex-slave (named ‘Buck’) who helps ‘massa’. Yeesh…

A gross of $2,900,000 marked 66th place in 1936, jostling for attention with a dozen notable pictures that centered around some aspect of Americana. With Harry Carey, Francis Ford, Francis McDonald (as Booth), Arthur Byron, Paul Fix, J.M. Kerrigan, Jack Pennick. 96 minutes.

Ford’s best biographer (with apologies to Scott Eyman), Joseph McBride, on this movie: “Ford and cameraman Bert Glennon depict Dr. Mudd’s nightmarish ordeal in military court and prison with starkly expressionistic camera angles, subtly distorting wide-angle lenses, and heavily shadowed compositions. But this film’s Goya-esque vision of torture and suffering is conveyed with greater emotional urgency and less abstractions than was displayed in Ford’s more-lauded exercise in expressionism 〈The Informer〉. Shark Island does not dwell on pictorial effects for their own sake, but maintains the relentless narrative drive so characteristic of Zanuck’s filmmaking philosophy.” Though they battled vigorously, Ford and Zanuck made ten pictures together: canny and dynamic ‘DFZ’ was one of the few studio czars that prickly poet Ford had any respect for.

As for splitting hairs between emotional ‘truth’ and the non-fiction record, the famous line from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance was cine-gospel for Fordian Americana. My Darling Clementine for example is held in higher regard than The Prisoner Of Shark Island, but it’s about as close to the facts as Arizona is to Florida (come to think of it…?). One thing dramatic licensing of things that did happen not only makes for a fun, even inspiring piece of entertainment, it can also nudge a person to read up on the subject, and not just animate your knowledge base but deepen your appreciation of the arts.

Someone (memory out for a walk) once made a wry jibe about the director credits for the epic How The West Was Won. Henry Hathaway directed three of the five segments of that giant-sized classic, George Marshall a fourth. The slimmest of the five was Ford’s contribution “The Civil War” and the joke was essentially “of course, who else?” In fact (darn’em), while it was one of his favorite subjects of study, he only visited it in three movies: briefly in HTWWW, in this postwar story of Dr. Mudd and full-on just in 1959’s The Horse Soldiers. Print the facts.