THE STEEL HELMET was the first movie made about and during the Korean War, coming out in January of 1951, a little over seven months since the conflict erupted. More interesting is that its success—critics and studio honchos took notice and the public lined up—announced its maverick auteur as someone to look out for. Pugnacious provocateur Samuel Fuller was 38 when he wrote, produced & directed this in-yer-mug combat saga, taking just ten days to shoot the 85-minute firecracker in the hills around L.A. and on a shoestring budget of $104,000. Fuller had been 32 when he hit the beach in Normandy, considerably older than most of his comrades. A reporter at 17, he’d been writing for motion pictures since he was 22. His first two as director (I Shot Jesse James and The Baron Of Arizona) didn’t ripple but he fired a bullseye with #3: The Steel Helmet grossed $2,000,000. At the end of the year Fuller doubled down with the superior, also Korea-set Fixed Bayonets!, which did twice as well. *

“If you die, I’ll kill yuh!”

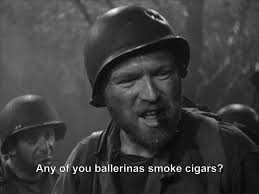

‘Sgt. Zack’ (Gene Evans), a grizzled WW2 vet, finds himself dog-tag deep in another struggle when he’s the sole survivor of a massacred unit. Helped by a friendly, English-speaking South Korean orphan, a plucky kid he nicknames ‘Short Round’, Zack soon encounters a small patrol of fellow G.I.s’, led by inexperienced ‘Lt. Driscoll’ (Steve Brodie, a fave getting a lot of work in the era). They include African-American medic ‘Cpl. Thompson’ (James Edwards, the go-to guy for playing black military characters in the day) and Zack’s old buddy ‘Sgt. Tanaka’ (Richard Loo, always welcome), Japanese-American Nisei with battle skills from the earlier war. Tasked with holding an abandoned Buddhist temple for an observation post, they are soon under attack from outnumbering North Korean units.

War may be hell, but in many movies—and Fuller’s no shrinking violet about it in his—it’s also a platform for ‘Who are We/What’s this all About’ speeches, either pitched from a rah-rah flag-waving angle or a this-is-insanity guilt zone. Sometimes both at once. Fuller certainly knew the terrain, peppering his script/s with authentic lingo, but he also was given to going flamboyantly overboard, often throwing every philosophical dart that irked or fed him. I recall seeing this gritty little bruiser as a kid (way before developing any historical/political kitbag), back in the Cold War days (the first Cold War that is) when it was accepted that the Commies were coming and “we” had to mow ’em down. Watched fresh six decades later, some of it holds up: offbeat Evans is excellent, Brodie a decent guy for once, the bleak tone of remorselessness, the sound effects. Much dates badly: silly secondary characters, mostly cheesy action, the cardboard production values, the piling on of pointed blather. Critics love it to pieces (I read one talking about how “realistic” it was and couldn’t help but guffaw, betting my last K-ration and carbine clip that they’d never been closer to combat than their computer monitor) but much as we like a lot of Sam Fuller’s platoon of melodramatic pictures we also temper praise with head-shakes over a tendency to excess.

With William Chun (‘Short Round’), Robert Hutton (lugging an accordion–please, Sam), Richard Monahan (as ‘Baldy’, hard to take whiner), Harold Fong (the North Korean captive, filled with speeches), Sid Melton (death scene milked like the last cow in the 38th parallel).

* Quotable Fuller: “The only way to bring the real experience of war to a movie audience is by firing a machine gun above their heads during the screening.”

Other soldier salvos from G.I. Sam came via China Gate (1957), Verboten! (1959), the excellent Merrill’s Marauders (1962) and his best-received barrage, 1980s salute The Big Red One.

Evans, 28, had been in bit parts for four years before Fuller gave him this lead role. He’d would work for him again in Fixed Bayonets!, Park Row, Hell And High Water and Shock Corridor.

The above figure on gross comes from Cogerson: several sites suggest it was three times higher, which we find unlikely.