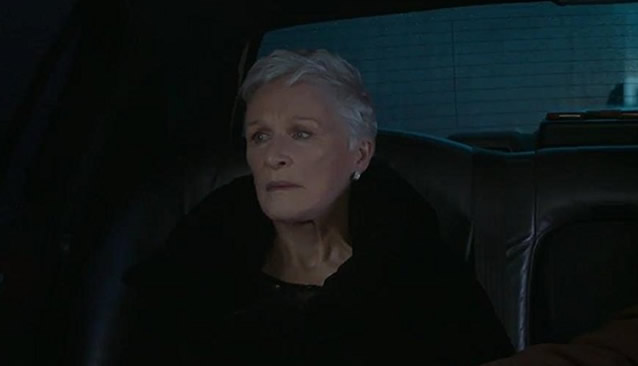

THE WIFE isn’t a happy drama for the characters involved, but the acting and writing make for a most-welcome experience for thoughtful, semi-literate adults in the audience, usually left wondering if every new movie will be slanted to 12-year-olds. Though this 2017 pleasure only scratched $18,400,000 and 127th place for the year in terms of money and exposure, it did garner Glenn Close a well-deserved Oscar nomination (her seventh) and pair her with another estimable pro, Jonathan Pryce. Close didn’t win, yet again, but by watching her in this, you will. *

In the early 90s, celebrated author and university professor ‘Joseph Castleman’ (Pryce) wins the Nobel Prize for Literature. During the trip to Stockholm to receive the honor, ‘Joan’ (Close), Joseph’s wife of more than three decades, finally & fully comes to grips with the lie/s that have marked their life together, not least those centered on actual talent and due credit. Scurrilous, dogged biographer ‘Nathaniel Bone’ (Christian Slater) tags along, as does their grown son (Max Irons), sidelined by the father’s fame. Flashbacks to Joseph’s and Joan’s meeting in the late 1950s illuminate their eventual dilemma.

Set in Stockholm, but filmed in Glascow, Scotland, it is the first English-language film for Swedish director Björn L. Runge, with a script by Jane Anderson, from a 2003 novel by Meg Wolitzer. Wolitzer’s 219-page book is described in book reviews as acerbically funny, but the 99-minute film (just the right length), while certainly stoked with wit, lends itself to quiet rage sublimated by a lifetime of civilized fraud. Know any marriages like that?

Peeling the love & loyalty onion here doesn’t entail the skin-shredding fireworks of Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf or the salt-in-burn battles on Revolutionary Road, but the cuts are scalpel precise, wounds deep, scars lasting. With actors so capable of razor-thin nuance as Close and Pryce, radiating emotional intelligence and command of craft, the painful exorcism of partners in the crime of self-deception becomes a feast for those famished from a cinema diet of reconstituted flash and trash. Score one for the grown-ups.

With Annie Stark (the 29-year-old daughter of Glenn Close, arresting as young Joan), Harry Lloyd, Karin Franz Körloff, and Elizabeth McGovern. Max Irons is the son of Jeremy Irons.

“There’s nothing more dangerous than a writer whose feelings have been hurt.”

* Close, but no cigar. That fits, in a movie about a woman overlooked. Glenn on the Oscar roster—as Best Supporting Actress: The World According To Garp (1982), The Big Chill (1983), The Natural (1985). As Best Actress: Fatal Attraction (1987), Dangerous Liaisons (1988), Albert Nobbs (2011) and The Wife (2017). She’s got 3 Emmy’s, 3 Tony’s and 3 Golden Globes. Quote Close: “I’ve often been mistaken for Meryl Streep, although never on Oscar night.” In 2020, she’ll only be 73, so we won’t give up the ship.

Meanwhile, back under the ceiling: the internationally used adage “Behind every successful man, there is a woman” can’t be pinned down to any one sage from a definite place in a particular time period, but it’s rather amusing to see all the opinions on it seething through the all-knowing, all-confusing ether of the Net. Why not credit Lucille Ball and then everyone who doesn’t know each other can argue about something else?

Jane Anderson’s screenplays include The Positively True Adventures of the Alleged Texas Cheerleader-Murdering Mom, It Could Happen To You, How To Make An American Quilt, and The Prize-Winner of Defiance Ohio. Each reward a view.

Meg Wolitzer, as of 2019, has written ten novels. We include a germane link here— https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/01/books/review/on-the-rules-of-literary-fiction-for-men-and-women.html