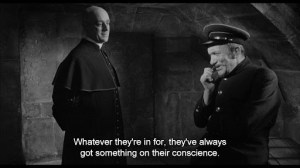

THE PRISONER is ‘the Cardinal’ (Alec Guinness), a revered Catholic clergyman being raked over the psychological coals by ‘the Interrogator’ (Jack Hawkins), who means to break him down to confess for a show trial in a totalitarian state. The country is unnamed but in 1955 this was accepted as an Eastern Bloc satellite state subservient to the Soviet Union. Praised in Britain, it made but a ripple across the pond in Red-fearing America, $800,000 placing in cell #182. It also managed the neat feat of being knocked in Ireland as pro-Communist, dinged at Cannes for being anti-Communist, banned in Venice as “so anti-Communist that it would be offensive to Communist countries”, while other Italians carped it was anti-Catholic. With that many consciences bruised someone must have been doing something right.

“Every living soul in that sleeping city down there could be broken, if they had to be. The softer the mind, the more sensitive the conscience, the more surely they must be broken. That’s the fascination – and the pity of it.”

Bridget Boland’s screenplay adapted her play, with Guinness, 41, repeating his stage role, Peter Glenville (Becket, The Comedians) directing both. It was the second time Guinness and Hawkins, 44, worked together, having done Malta Story in 1953. They’d later go big-time international with The Bridge On The River Kwai and Lawrence Of Arabia, though not sharing scenes together in those titans. Boland’s battle of wits and wills was based on the brutish, farcical show trials of cardinals in Hungary and Croatia, and clearly has a Cold War/Orwellian face atop its thoughts, but the theme of ideological functionaries wielding state power against individual spirits and the spark of resistance goes as far back as caves. Tragically, it’s/they’ve never left us (alone). *

“They want me to take my own life, so they can say I committed the last cowardice of all.”

It is stagy (fitting in that the torment is stage-managed for effect of intent) and the clever dialogue exchanges ‘feel’ literary rather than natural, but with actors as vital and with voices as mellifluous as Guinness and Hawkins we gladly accept the artificiality of the framework. Adding a just right touch of ‘earthy commoner’ is Wilfrid Lawson, delightfully real as ‘The Jailer’, making a baklava bite of every line. The only hangup is a forced and shallow subplot shoehorned in for ‘The Guard’ (Ronald Lewis) and ‘The Girl’ (Jeanette Sterke).

“Mustn’t let a little squeamishness spoil your fun.”

Shot mainly in England, with some exteriors done in Belgium, in Ostend and Bruges. Alternate facts sources give 91 and 95 minutes; either could be trimmed by ten if the bland subplot of guard and girl was excised. With Raymond Huntley (blithely smug), Kenneth Griffith (holding off on overplaying), Mark Dignan, Gerard Heinz and the ubiquitous mug of Percy Herbert.

* Bridget Boland, 1913-1988—“Although I hold a British passport I am in fact Irish, and the daughter of an Irish politician at that, which may account for a certain contrariness in my work. Many playwrights have become screenwriters; so I was a screenwriter and became a playwright. Most women writers excel on human stories in domestic settings: so I am bored by domestic problems, and allergic to domestic settings. I succeed best with heavy drama (The Prisoner), so I can’t resist trying to write frothy comedy (Temple Folly). By the time you have written half a dozen plays or so you began to realize you are probably still trying to write the one you started with. However different I begin by thinking is the theme of each, I find that in the end every play is saying: “Belief is dangerous”. Boland also wrote the screenplay to the 1940 version of Gaslight, helped adapt the 1956 War And Peace and co-wrote the script for Anne Of The Thousand Days.