A FISTFUL OF DOLLARS turned into a vault load by the time Per un pugno di dollari, a 1964 Italian-German-Spanish ode to/revamp/looting of traditional American westerns had swept thru Europe and galloped into the States in 1967. Eventually, with re-releases it swiped $14,500,000 in North America, 73% of the total worldwide haul, vanquishing the sparse spread of lira, D-marks and pesetas—less than $225,000 worth—begged & borrowed make it. Beyond filling the bread basket, the stylish and subversive mixture of silliness and sadism secured a wacky subgenre, revitalized the movies oldest one, and in concert with two bigger and better sequels that also invaded America in ’67, firepowered several careers from stasis to stardom. *

“Get three coffins ready.”

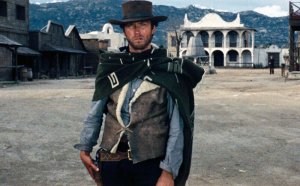

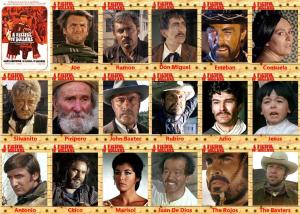

The Mexican town of ‘San Miguel’ near the US border, is run by competing gangs of smugglers, two families that—when not decimating each other and abusing the hapless citizens—play off the government cavalry and that of the Americanos against one another, running guns to tribes and allied outlaws who fight with both. A gringo stranger (Clint Eastwood)—later identified only as ‘Joe’, but whether that’s accurate is iffy—shows up, easily plugs a slew of slimes in a gunfight, and proceeds to try and deal with both factions. Joe survives a beating that would maim a brontosaurus, the casualty count reaches wipeout level, and eventually the worst of the baddies, psychotic bastardo ‘Ramón Rojo‘ (Gian Maria Volonté) will learn the impact differential between a Winchester and a Colt. 45. El hard way.

The script, perjured adapted Akira Kurosawa’s 1961 Yojimbo, was a mashup of inputs from Leone, Jaime Comas Gil, A. Bonzzoni and Victor Adres Catena. Besides taciturn and rangy Clint, the cast was Italian, German, Spanish and Austrian. It was shot in southern Spain not only since the arid landscapes could blink & pass for the US southwest or Mexico but because it was 75% cheaper to film in Spain rather than Italy. *

At 34, Eastwood, still in TV harness on Rawhide (217 episodes, 7½ seasons, 1959 thru 1965) took the gig for $15,000, a vacation in Europe and an amiable “if it works, swell; if not, swell” attitude. He self-styled the costume that became the famed and emblematic look of ‘The Man With No Name’. Pre-Rawhide, none of his eleven bit parts in movies had shown any promise, and he doesn’t have to do much in this other than look grim, dry-deliver the inane dialogue (‘looped’ later) and appear somehow logic-suspending-acceptable when mowing down four or five sweaty, smirking hombres, standing yards apart, forty feet away, with gunshot noises louder than something blasted from the turrets of the USS New Jersey. Out of the essential absurdity of this brutal starter pistol would emerge one of the most surprising, celebrated and enduring careers in movie history, legend writ large.

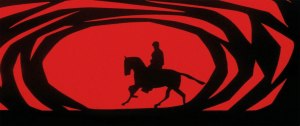

That sonic boom gunfire does sound cool, though, and both the audio (non-spoken, the dialogue is awful) and the visual are the key selling points of Leone’s operatic overkill. That a new sheriff (or several) was in town becomes apparent from the first minute with the startling titles designed by Iginio Lardani, done with a flourish to rival the other greats of the day, Saul Bass and Maurice Binder. Behind the animation is one of the indisputably outstanding elements of this movie, the immediately arresting music from Ennio Morricone. The 35-year-old had composed eighteen scores prior to this, but his teaming with Leone’s trilogy (and further works) introduced him internationally. His surging, haunting main theme here would be bettered in For A Few Dollars More and then reach stratospheric glory on The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Whetting the eyes, Leone saw that cinematographer Massimo Dallamano’s extreme closeups, allied with the editing that held the shots for extra long beats, achieved the feel of portraiture, making something simple, tight and immediate exude a sense of the grand, portentous and epic.

99 minutes with stares, snarls, snickers and spasms from Marianne Koch (on hand so the otherwise mercenary Man With No Name can show at least a glimmer of gallantry beneath his scowls),Wolfgang Lukschy, Sieghardt Rupp, Joseph Egger, Antonio Prieto, Jose Calvo, Benny Reeves, Mario Brega and Aldo Sambrell.

* Over six hundred westerns were stampeded out of Europe between 1960 and 1970, 83% coming from Italy, the Germany’s (East & West) providing most of the remainder. While Sergio and Clint weren’t first on the scene, the huge triple impact of this, For A Few Dollars More (made in ’65) and the grand-scale The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (from ’66) locked & loaded “spaghetti westerns” as a thing: scorned by some, cherished by many, ultimately accepted by pretty much everybody. We gave the world our westerns: they loved them, and gave ’em back. Foreign policy…uh, something else again.

** Banzai charges—Kurosawa and Toho Intl. sued Leone, with Akira pronouncing Sergio’s as “a fine movie, but it was my movie”. Leone settled out of court, samurai sliced for 15% of the global profits. He asserted (critic Christopher Frayling insists as well) that his inspiration was partly Yojimbo, part Dashiell Hammett’s 1929 novel “Red Harvest”, both owing a debt to “Servant Of Two Masters”, a 1746 play from Carlo Goldoni.