A MAN CALLED HORSE was a big deal in 1970, a compelling, exciting, visually striking western adventure made memorable for a grip-armrest-grit-teeth sequence of primitive bravery ritual, one of those magic movie moments that could—in the revisionist, upend the genre spirit of the day—have you feeling good about feeling bad, smugly ‘enlightened’ when you talked it over later. It was, and is, all of those. It’s also a crock.

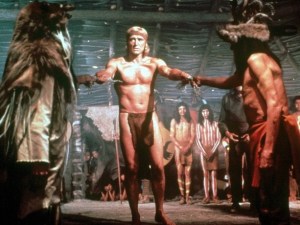

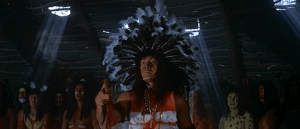

1825. English lord ‘John Morgan’ (Richard Harris, 39), on a hunting trip in the untamed West, is captured by a band of Sioux braves and taken, naked and battered, to their camp. He’s presented as a gift laborer to ‘Buffalo Cow Head’ (Judith Anderson, 71), mother of the chief ‘Yellow Hand’ (Manu Tupou, 33) and maiden daughter ‘Running Deer’ (Corinna Tsopei, 24). After ample abuse, with escape highly unlikely, Morgan, mockingly christened ‘Horse’, determines to survive, adapt and eventually win his freedom. First, unarmed, he kills two Shoshone scouts in hand-to-hand combat. Then he asks for the hand of Running Deer (one look at Tsopei makes that readily understandable) but before their tepee union is consummated he must undergo the Sun Dance ceremony. The agony of that passage into bloodied-brother acceptance from the tribe is followed by the return of the Shoshone—in force.

Directed with verve by Elliot Silverstein (good job on Cat Ballou, lame on The Happening, Nightmare Honeymoon and The Car), the script done by Jack DeWitt had ancestry arrows in its quiver; Dorothy M. Johnson’s 1950 short story was first filmed as a 1958 episode of Wagon Train, with Ralph Meeker as ‘Horse’. Some location shooting was done in South Dakota (Sioux territory) and Arizona with the bulk of the plush $5,000,000 production accomplished down in the Mexican states of Durango, Chihuahua and Sonora. The cinematography from Robert B. Hauser is striking and Leonard Rosenman’s score fits the intensity. Harris and the others give impassioned performances, the action scenes are fierce and the agonizingly vivid Vow to the Sun ritual is transfixing, grueling to witness, hard to forget. Supposedly 25 historians were consulted to insure accuracy in the detailing of dwellings, artifacts, ceremonial paint, masks, headdresses and the like. The release came in a year that saw portions of the Native American experience parlayed on screen in Little Big Man (a winner, 1970’s 6th biggest hit), Soldier Blue (ultra-violent, insultingly anachronistic, 74th place) and Flap (just plain dumb, 112th). Audiences flocked to see haughty Harris transform to heroic Horse, making this the year’s 18th most attended movie, with the global gross reaching $44,000,000.

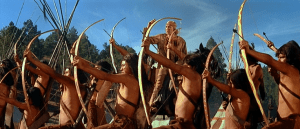

AND YET—hold your Horse, man. Civil disobedience ambushed the world premiere in Minneapolis with picketing, AIM (American Indian Movement) members blocked the ticket office, there were even bomb threats. While—though wokies won’t wake to it—the ordeals undergone by captives of some tribes could be truly horrible, the gory rite as depicted in the movie was not practiced by the Sioux. The final battle with the Shoshone is appropriately furious, but also spurious, with the Euro-bred Brit taking instant command and ‘teaching’ the Sioux how to line up infantry-style to repel a mounted charge: puh-leeze. A handful of Native Americans served as extras along with a mostly Mexican contingent, while the leads were put over by an Australian (Anderson), a Fijian (Tupou), and a Greek (Tsopei). The imposing Tupou had acted with Harris on the epic Hawaii and the stunningly pretty Tsopei had been 1964’s Miss Universe. Granted, she’s ravishing enough to be mutilated over, even if the screenplay serves not truth but trend.

114 minutes with Jean Gascon (likable as longtime French prisoner ‘Batise’, enduring captivity as a hamstrung clown), Lina Marin, Eddie Little Sky (one actual Oglalla Lakota in the cast), Dub Taylor, Michael Baseleon, Iron Eyes Cody, James Gammon and Manuel Padilla Jr. Followed seven years later by The Return Of A Man Called Horse, and six after that in Triumphs Of A Man Called Horse. *

* Though he’s very good and obviously committed this was not Harris’s best performance (This Sporting Life) or biggest box office success where he had the lead role (Camelot) but thanks to the iconic ritual sequence it is probably his most famous film. 1970 was a big year for that wild lad, with two more high-profile epics, Cromwell and The Molly Maguires. He also did a quick frontier-set follow-up, again written by Jack DeWitt, 1971’s Man In The Wilderness. It did reasonable business but nothing close to ‘Horse’.