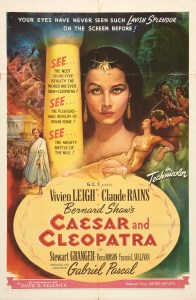

CAESAR AND CLEOPATRA, after commencing their empire-embellishing dalliance around four decades B.C., had their divines-entwine epic pass thru scribes, poets, historians and eventually playwrights from Shakespeare to George Bernard Shaw, who wrote the 1898 play that ultimately begat a 1945 movie directed by Gabriel Pascal. Still kicking and prickly at 89, Shaw is credited for the script.

Made under difficult conditions (chiefly the still-raging WW2, secondarily personal issues from a troubled and troubling star) its already hefty budget ballooned until the cost reached a staggering $5,200,000, surpassing Gone With The Wind as the most expensive production yet mounted. That was soon topped by another ill-fated-lovers epic, Duel In The Sun. But GWTW and ‘Duel’ were enormous hits, and Pascal’s slo-boat to Shaw sank under a sandstorm of red ink. It only made about $1,400,000 in Britain, too occupied recovering to pay much attention to a windy satire on a past empire’s fiddling. Upon emigrating to the States the following year, trimmed five minutes to 123, it grossed $6,200,000, ranking 51st for the year. But with the drag from that Nile-sized tribute it fell, impaled upon its own wit-bangled sword. A sole Oscar nomination came for the Art Direction.

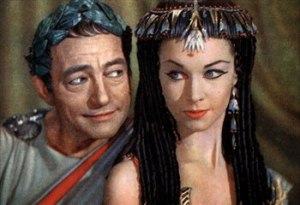

Seeking to end the Roman Civil War and bring rule-divided Egypt into line, Julius Caesar (Claude Rains) boldly strides onto the sands of the pharaohs. Upon encountering the nubile but nervous queen-assumptive Cleopatra (Vivien Leigh), the middle-aged conqueror advises the fledgling femme fatale on how to rule. They talk things over. And talk, and talk, and…

The good—it looks fine in Technicolor, thanks to an amazing quartet of soon-to-be-world-famous cinematographers: Frederick Young, Robert Krasker, Jack Cardiff and Jack Hildyard. Shavian pith rolls off the tongues of an impressive roster of acting talent, those already proven (Rains, Leigh) and those about to mark their marks. Best line: “And so to the end of history, murder shall breed murder, always in the name of right, and justice, and peace, until the gods create a race of men that can understand.” Though written 47 years earlier, that carried extra poignancy when delivered on screen at the end of history’s biggest preventable slaughter.

The fly in the fig jar: it doesn’t take too long before the constant conversations wear out a fanning whisk as you wait for something to happen. Pace = snails. Despite the expense, the sets look stagy and obvious (that sphinx is cool, though), the crowds merely noisy, costuming unimpressive. The constant declaiming comes off like assiduously rehearsed dialogue rather than convincing human speech, and the underlying Pygmalion aspect—wise older man teaches naive young beauty how to behave—doesn’t sell as well as it postures to. The density of all the political back & forth and bitchy name-dropping blithely presumes that an intended audience was educated enough to know something beyond a few famous names. That was doubtless true for the upper class in England, but one can’t help wondering if the average Cockney laborer knew anything more about Egypt other than that it was a place they might end up dying for in order to protect it from Adolf—and incidentally save that canal for access to ‘British’ India. Hey, hold your buggy whip, sire—if Shaw can use a sandbox for a soapbox, so can a colonial mug; granted somewhat after the fact.

Two schools on this one. A good portion of those who seek it out will tire of the self-bemused nattering and wonder if anything like a battle will ever show up. Or a swordfight? A parade? A dance of maidens? Look elsewhere.

On the other scroll, for many it’s enough just to see and listen to so many bygone favorites. Diction-lord Rains is always a pleasure, and mischievous Leigh captures attention effortlessly. At hand are up-and-coming Stewart Granger, injecting some needed brio and brawn as lusty rogue Apollodorus, and stalwarts such as Flora Robson (having fun as witchy ‘Ftatateeta’, Cleo’s chief servant), Francis L. Sullivan (pompous eunuch Pothinus), Cecil Parker (‘Britannus’), and Basil Sydney (‘Rufio’). Prissy fossil Ernest Thesiger wasps to form as Theodotus, teacher to Cleo’s bratty kid brother Ptolemy, played with gusto by 15-year-old Anthony Harvey, who as a grownup would direct other squabbling royals in The Lion In Winter.

Also briefly on view are newcomers Michael Rennie, Leo Genn, Stanley Holloway and Felix Aylmer. Sixteen-year-old Jean Simmons is in there, uncredited, plucking a harp.

* Shaw, on the result: “a poor imitation of Cecil B. DeMille”. He was referring to DeMille’s gaudy 1934 turn at Cleopatra, which, unlike this chatter-buried movie—moved—and was a lot of fun. Passing on in 1950, GBS missed out on 1963’s titan Cleopatra, perennially underrated. Unlike those two, the Shaw-Pascal version entirely leaves out Mark Antony (apart from a one-sentence mention at the finish). Those keen on gathering papyrus from the film versions are urged to dig up the superb HBO series Rome for a fresh, raw take on an age-old-old-old story.