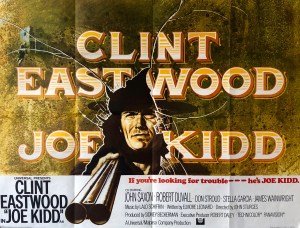

JOE KIDD, a 1972 Clint Eastwood western set in early 1900’s New Mexico, had originally been titled ‘Sinola’, after the (fictional) town where some of it takes place. The professional yet pedestrian results may as well have been called ‘Joe Blow’ or ‘Just Kidding’ for the non-fuss it made, a letdown considering the star, director and writer. It has its moments, thanks to a few droll bits in the supporting cast, the location scenery and an unexpected nutty finish involving using a train as a weapon, but character inconsistence, tone shifts, and a lurking sense of pointlessness make it mainly a check-off-the-list item for Clint fans; at least it beats Two Mules For Sister Sara, High Plains Drifter or Pale Rider and is only 88 minutes long. *

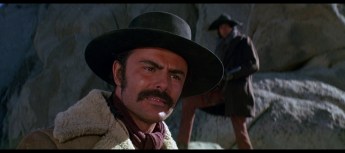

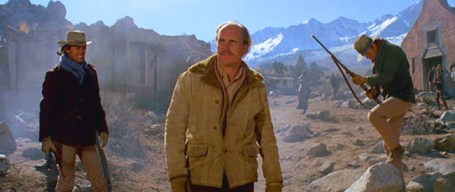

New Mexico Territory, early 1900s. Tracker, bounty hunter, generally unruly ‘Joe Kidd’ (Eastwood, calmly lethal) reluctantly joins a posse led by landowner bigshot ‘Frank Harlan’ (Robert Duvall, in ‘country’ mode, nasty version) to go after Mexican-American revolutionary ‘Luis Chama’ (John Saxon, in seething mood) whose justified desire to right Anglo wrongs (like stealing land titles) conflicts with his manner: audience sympathy for Chama evaporates when he tells his supportive girlfriend “I do not care what you think. I take you along for cold nights and days when there is nothing to do. Not to hear you talk.” Much gunfire results, because we didn’t plunk down our legal tender to watch acreage arguments play out in something as useless as court.

Western veteran Elmore Leonard (3:10 To Yuma, Hombre) wrote the script. Action ace John Sturges directed, shooting on handsome if chilly locations in the California Sierra’s around Bishop and at recognizable standby ‘Old Tucson’ in Arizona. Sturges, hoping for a lighter tone, was at variance with the star, opting for something harsher; the uneasy script and editing reflects both without meshing them effectively. Lalo Schifrin’s score doesn’t saddle comfortably, the noisy action scenes are competently performed but haphazardly placed, and the ram-a-train-thru-town finale is modestly wild but also feels like just a quick fix to get out of a dead-end scenario. **

Clint clout ensured that $17,200,000 came in, nestling at #24 in ’72. Ducking or absorbing bullets, punches and insults: Don Stroud (mean of course), Stella Garcia, Paul Koslo, James Wainwright (best man in the cast, his casual iciness chuckle worthy), Gregory Walcott, Lynne Marta, Dick Van Patten, John Carter, Pepe Hern, Ron Soble, Clint Ritchie and Chuck Hayward.

* East (wood) meets West: stick with The Good, The Bad And The Ugly, The Outlaw Josey Wales and Unforgiven.

** Co-opt this—Leonard, after one of the producers (Sidney Beckerman or Robert Daley) would switch out his material and substitute their own: “I’d cross out everything he wrote and put my own dialogue back in. The producer never said a thing—I think he just liked to cross things out.”

Casualty count: Eastwood’s wishes with editing superseded Sturges to the point where Sturges and his longtime editor Ferris Webster (The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape) parted company after 14 movies and decades of friendship, never speaking again, even though they lived a few blocks from each other. Webster switched hitches from a director on the downslope to a star on fire, and cut 14 more Clint pix.